|

Solutions to the Laplace equation in cylindrical coordinates have wide applicability from fluid mechanics to electrostatics. Applying the method of separation of variables to Laplace's partial differential equation and then enumerating the various forms of solutions will lay down a foundation for solving problems in this coordinate system. Finally, the use of Bessel functions in the solution reminds us why they are

synonymous with the cylindrical domain.

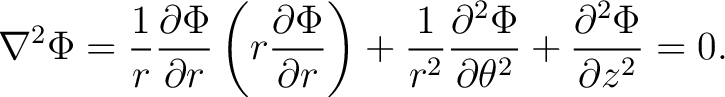

Beginning with the Laplacian in Cylindrical Coordinates, apply the operator to a potential function and set it equal to zero to get the Laplace equation

|

(1) |

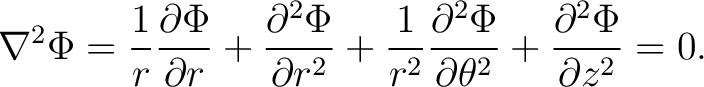

First expand out the terms

|

(2) |

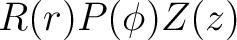

Then apply the method of separation of variables by assuming the solution is in the form

Plug this into (2) and note how we can bring out the functions that are not affected by the derivatives

Divide by

and use short hand notation to get and use short hand notation to get

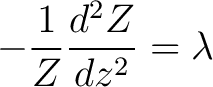

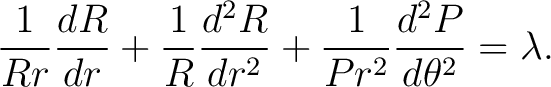

“Separating” the z term to the other side gives

This equation can only be satisfied for all values if both sides are equal to a constant,  , such that , such that

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

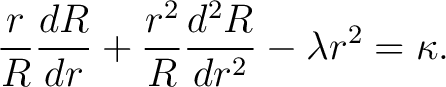

Before we can focus on solutions, we need to further separate (4), so multiply (4) by

Separate the terms

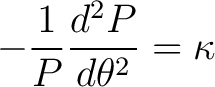

As before, set both sides to a constant,

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

Now there are three differential equations and we know the form of these solutions. The differential equations of (3) and (5) are ordinary differential equations, while (6) is a little more complicated and we must turn to Bessel functions.

Following the guidelines setup in [Etgen] for linear homogeneous differential equations, the first step in solving

is to find the roots of the characteristic polynomial

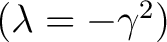

Although, one can go forward using the square root, here we will introduce another constant,  to imply the following cases. So if we want real roots, then we want to ensure a negative constant to imply the following cases. So if we want real roots, then we want to ensure a negative constant

and if we want complex roots, then we want to ensure a positive constant

Case 1:

and real roots and real roots

. .

For every real root, there will be an exponential in the general solution. The real roots are

Therefore, the solutions for these roots are

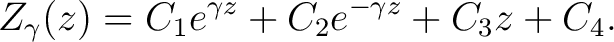

Combining these using the principle of superposition, gives the general solution,

|

(7) |

Case 2:

and complex roots and complex roots

. .

The roots are

and the corresponding solutions

Combining these into a general solution yields

Azimuthal solutions for

are in the most general sense obtained similarly to the axial solutions with the characteristic polynomial

Using another constant,  to ensure positive or negative constants, we get two cases. to ensure positive or negative constants, we get two cases.

Case 1:

and real roots and real roots

. .

The solutions for these roots are then

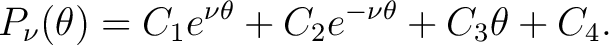

Combining these for the general solution,

|

(8) |

Case 2:

and complex roots and complex roots

. .

The roots are

and the corresponding solutions

Combining these into a general solution

For the first glimpse at simplification, we will note a restriction on  that is used when it is required that the solution be periodic to ensure that is used when it is required that the solution be periodic to ensure  is single valued is single valued

Then we are left with either the periodic solutions that occur with complex roots or the zero case. So not only

but also  must be an integer, i.e. must be an integer, i.e.

|

(9) |

Note, that  , is still a solution, but to be periodic we can only have a constant , is still a solution, but to be periodic we can only have a constant

The radial solutions are the more difficult ones to understand for this problem and are solved using a power series. The two types of solutions generated based on the choices of constants from the  and and  solutions (excluding non-periodic solutions for solutions (excluding non-periodic solutions for  ) leads to the Bessel functions and the modified Bessel functions. The first step for both these cases is to transform (6) into the Bessel differential equation. ) leads to the Bessel functions and the modified Bessel functions. The first step for both these cases is to transform (6) into the Bessel differential equation.

Case 1:

, ,

. .

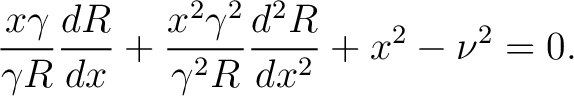

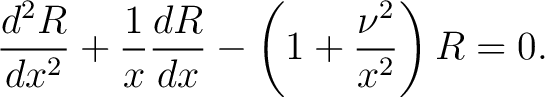

Substitute  and and  into the radial equation (6) to get into the radial equation (6) to get

|

(10) |

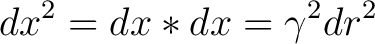

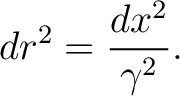

Next, use the substitution

Therefore, the derivatives are

and make a special note that

so

Substituting these relationships into (10) gives us

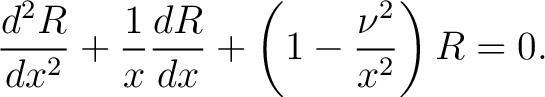

Finally, multiply by  to get the Bessel differential equation to get the Bessel differential equation

|

(11) |

Delving into all the nuances of solving Bessel's differential equation is beyond the scope of this article, however, the curious are directed to Watson's in depth treatise [Watson]. Here, we will just present the results as we did for the previous differential equations. The general solution is a linear combination of the Bessel function of the first kind

and the Bessel function of the second kind and the Bessel function of the second kind

. Remebering that . Remebering that  is a positive integer or zero. is a positive integer or zero.

|

(12) |

Bessel function of the first kind:

Bessel function of the second kind (using Hankel's formula):

For the unfortunate person who has to evaluate this function, note that when  , the singularity is taken care of by replacing the series in brackets by , the singularity is taken care of by replacing the series in brackets by

Some solace can be found since most physical problems need to be analytic at  and therefore and therefore

breaks down at breaks down at  . This leads to the choice of constant . This leads to the choice of constant  to be zero. to be zero.

Case 2:

, ,

. .

Using the previous method of substitution, we just get the change of sign

|

(13) |

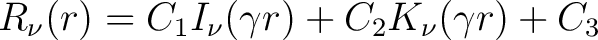

This leads to the modified Bessel functions as a solution, which are also known as the pure imaginary Bessel functions. The general solution is denoted

|

(14) |

where  is the modified Bessel function of the first kind and is the modified Bessel function of the first kind and  is the modified Bessel function of the second kind is the modified Bessel function of the second kind

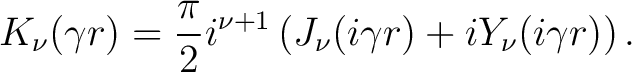

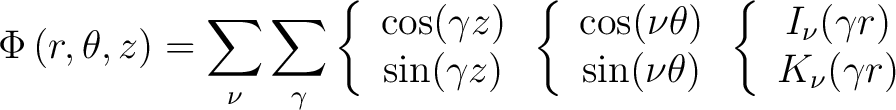

Keeping track of all the different cases and choosing the right terms for boundary conditions is a daunting task when one attempts to solve Laplace's equation. The short hand notation used in [Kusse] and [Arfken] will be presented here to help organize the choices as a reference. It is important to remember that these solutions are only for the single valued azimuth cases

. .

Once the separate solutions are obtained, the rest is simple since our solution is separable

so we just combine the individual solutions to get the general solutions to the Laplace equation in cylindrical coordinates.

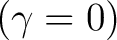

Case 1:

, ,

. .

|

(15) |

Case 2:

, ,

. .

|

(16) |

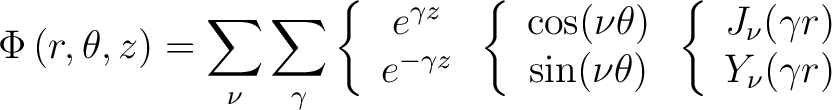

Interpreting the short hand notation is as simple as expanding terms and not forgetting the linear solutions, i.e.

. As an example, case 1, expanded out while ignoring the linear terms would give . As an example, case 1, expanded out while ignoring the linear terms would give

|

(17) |

- 1

- Arfken, George, Weber, Hans, Mathematical Physics. Academic Press, San Diego, 2001.

- 2

- Etgen, G., Calculus. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1999.

- 3

- Guterman, M., Nitecki, Z., Differential Equations, 3rd Edition. Saunders College Publishing, Fort Worth, 1992.

- 4

- Jackson, J.D., Classical Electrodynamics, 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1975.

- 5

- Kusse, Bruce, Westwig, Erik, Mathematical Physics. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1998.

- 6

- Lebedev, N., Special Functions & Their Applications. Dover Publications, New York, 1995.

- 7

- Watson, G.N., A Treatise on the Theory of Bessel Functions. Cambridge University Press, New York, 1995.

|