|

Consider the function

, the derivative of , the derivative of  with respect to time; one can say that the operator with respect to time; one can say that the operator

acting on the function acting on the function  yields the function yields the function

. More generally, if a certain operation allows us to bring into correspondence with each function . More generally, if a certain operation allows us to bring into correspondence with each function  of a certain function space, one and only one well-defined function of a certain function space, one and only one well-defined function

of that same space, one says the of that same space, one says the

is obtained through the action of a given operator is obtained through the action of a given operator  on the function on the function  , and one writes , and one writes

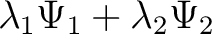

By definition  is a linear operator if its action on the function is a linear operator if its action on the function

, a linear combination with constant (complex) coefficients, of two functions of this function space, is given by , a linear combination with constant (complex) coefficients, of two functions of this function space, is given by

Among the linear operators acting on the wave functions

associated with a particle, let us mention:

- the differential operators

, ,

, ,

, ,

, such as the one which was considered above; , such as the one which was considered above;

- the operators of the form

whose action consists in multiplying the function whose action consists in multiplying the function  by the function by the function

Starting from certain linear operators, one can form new linear operators by the following algebraic operations:

- multiplication of an operator

by a constant by a constant  : :

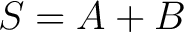

- the sum

of two operators of two operators  and and  : :

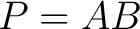

- the product

of an operator of an operator  by the operator by the operator  : :

Note that in contrast to the sum, the product of two operators is not commutative. Therein lies a very important difference between the algebra of linear operators and ordinary algebra.

The product  is not necessarily identical to the product is not necessarily identical to the product  ; in the first case, ; in the first case,  first acts on the function first acts on the function  , then , then  acts upon the function acts upon the function  to give the final result; in the second case, the roles of to give the final result; in the second case, the roles of  and and  are inverted. The difference are inverted. The difference  of these two quantities is called the commutator of of these two quantities is called the commutator of  and and  ; it is represented by the symbol ; it is represented by the symbol ![$[A,B]$ $[A,B]$](http://images.physicslibrary.org/cache/objects/588/l2h/img44.png) : :

![$\displaystyle [A,B] := AB - BA$ $\displaystyle [A,B] := AB - BA$](http://images.physicslibrary.org/cache/objects/588/l2h/img45.png) |

(1) |

If this difference vanishes, one says that the two operators commute:

As an example of operators which do not commute, we mention the operator  , multiplication by function , multiplication by function  , and the differential operator , and the differential operator

. Indeed we have, for any . Indeed we have, for any  , ,

In other words

![$\displaystyle \left [ \frac{\partial}{\partial x},f(x) \right ] = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$ $\displaystyle \left [ \frac{\partial}{\partial x},f(x) \right ] = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$](http://images.physicslibrary.org/cache/objects/588/l2h/img52.png) |

(2) |

and, in particular

![$\displaystyle \left [ \frac{\partial}{\partial x},x \right ] = 1$ $\displaystyle \left [ \frac{\partial}{\partial x},x \right ] = 1$](http://images.physicslibrary.org/cache/objects/588/l2h/img53.png) |

(3) |

However, any pair of derivative operators such as

, ,

, ,

, ,

, commute. , commute.

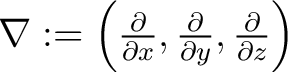

A typical example of a linear operator formed by sum and product of linear operators is the Laplacian operator

which one may consider as the scalar product of the vector operator gradient

, by itself. , by itself.

[1] Messiah, Albert. "Quantum mechanics: volume I." Amsterdam, North-Holland Pub. Co.; New York, Interscience Publishers, 1961-62.

This entry is a derivative of the Public domain work [1].

|