|

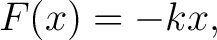

A system is said to be harmonic if its restoring force is exactly linear in the displacement from equilibrium. In one dimension,

|

(1) |

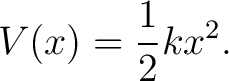

corresponding to the potential

|

(2) |

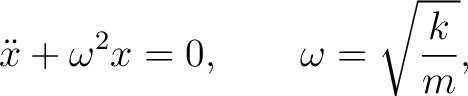

The equation of motion,

|

(3) |

has solutions that are purely sinusoidal. Harmonic systems possess several exceptional properties: amplitude-independent frequencies, exact superposition, closed classical orbits, and equally spaced quantum energy levels [1, 3].

These features make the harmonic oscillator a cornerstone of theoretical physics but also an idealization.

A system is anharmonic if its exact potential energy function deviates from a purely quadratic form.

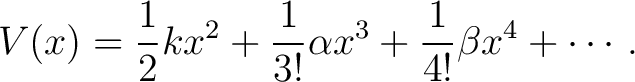

For a stable equilibrium at  , the potential can be expanded as , the potential can be expanded as

|

(4) |

The presence of any term beyond  constitutes anharmonicity. These higher-order terms imply that the restoring force is nonlinear in displacement, producing behavior fundamentally different from harmonic motion. constitutes anharmonicity. These higher-order terms imply that the restoring force is nonlinear in displacement, producing behavior fundamentally different from harmonic motion.

A common objection arises: since any smooth potential can be Taylor expanded about equilibrium, does anharmonicity represent anything physically distinct?

The resolution lies in distinguishing between approximation and structure.

A common objection arises: since any smooth potential can be Taylor expanded about equilibrium, does anharmonicity represent anything physically distinct?

The resolution lies in distinguishing between approximation and structure.

A system is harmonic if its exact potential is quadratic. A system is anharmonic if its exact potential contains higher-order terms, regardless of how small they may be.

The harmonic approximation truncates the expansion at second order. This approximation does not remove anharmonicity from the physical system; it merely neglects it. Anharmonic terms represent real interactions that cannot be eliminated by a change of variables or higher-order truncation.

Anharmonicity introduces effects absent in harmonic systems:

- Amplitude-dependent oscillation frequencies

- Asymmetric restoring forces

- Energy exchange between modes

- Breakdown of closed orbits

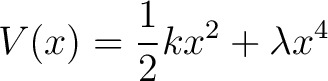

For example, the potential

|

(5) |

leads to a frequency shift proportional to the oscillation amplitude. This behavior is characteristic of nonlinear oscillators such as the Duffing oscillator [2].

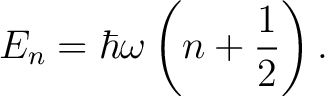

In quantum mechanics, harmonicity implies equally spaced energy levels,

|

(6) |

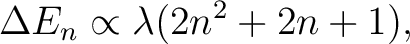

Anharmonic corrections destroy this uniform spacing. Using perturbation theory, a quartic correction produces energy shifts of the form

|

(7) |

which increase with quantum number[4]. This explains why molecular vibrational spectra exhibit overtones and anharmonic spacing.

Purely harmonic systems are rare in nature. Anharmonicity is essential for:

- Thermal expansion of solids

- Finite phonon lifetimes

- Molecular bond dissociation

- Nonlinear wave propagation

Thus, harmonic models should be viewed as leading-order approximations within a broader anharmonic framework [5].

Anharmonicity is not a mathematical inconvenience but a reflection of the nonlinear structure of physical interactions. While harmonic models offer clarity and solvability, anharmonic terms encode the corrections that make physical systems realistic. Understanding anharmonicity is therefore essential for both accurate modeling and physical insight.

- 1

- H. Goldstein, C. Poole, and J. Safko, Classical Mechanics, 3rd ed., Addison-Wesley, 2002.

- 2

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Mechanics, 3rd ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, 1976.

- 3

- D. J. Griffiths, Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed., Pearson, 2005.

- 4

- J. J. Sakurai and J. Napolitano, Modern Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed., Pearson, 2011.

- 5

- N. W. Ashcroft and N. D. Mermin, Solid State Physics, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976.

- 6

- M. L. Boas, Mathematical Methods in the Physical Sciences, 3rd ed., Wiley, 2006.

|