|

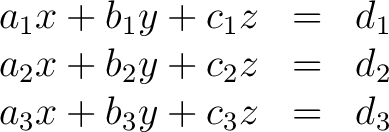

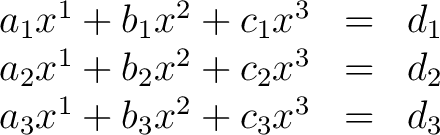

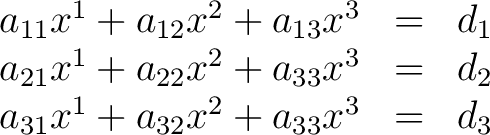

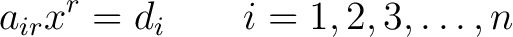

In much of the material of related to physics, one finds it expedient to adapt the summation convention first introduced by Einstein. Let us consider first the set of linear equations

|

(1) |

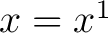

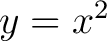

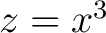

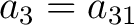

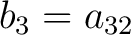

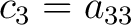

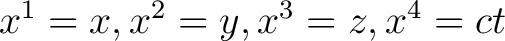

We shall find it to our advantage to set  , ,  , ,  . The superscripts do not denote powers but are simply a means for distinguishing between the three quantities . The superscripts do not denote powers but are simply a means for distinguishing between the three quantities  , ,  , and , and  . One immediate advantage is obvious. If we were dealing with 29 variables, it would be

foolish to use 29 different letters, one letter for each variable. The single letter . One immediate advantage is obvious. If we were dealing with 29 variables, it would be

foolish to use 29 different letters, one letter for each variable. The single letter  with a set of superscripts ranging from 1 to 29 would suffice to yield the 29 variables, written with a set of superscripts ranging from 1 to 29 would suffice to yield the 29 variables, written  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  . Our reason for using superscripts rather than subscripts will soon become evident. Equations (1) can now be written . Our reason for using superscripts rather than subscripts will soon become evident. Equations (1) can now be written

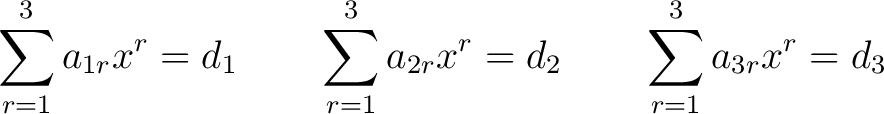

|

(2) |

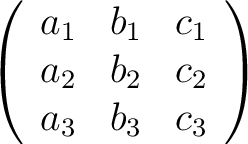

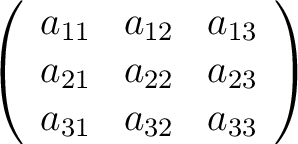

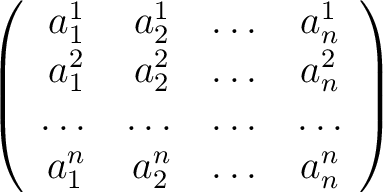

Equations (2) still leave something to be desired, for if there were 29 such equations, our patience would be exhausted in trying to deal with the coefficients of  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  . Let us note that in (2) the coefficients of . Let us note that in (2) the coefficients of  , ,  , ,  may be expressed by the matrix may be expressed by the matrix

|

(3) |

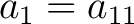

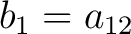

By defining

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, the matrix (3) becomes , the matrix (3) becomes

|

(4) |

One advantage is immediately evident. The single element  lies in the ith row and jth column of the matrix (4). Equations (1) can now be written lies in the ith row and jth column of the matrix (4). Equations (1) can now be written

|

(5) |

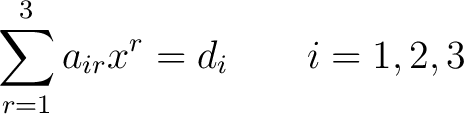

Using the familiar summation notation of mathematics, we rewrite (5) as

|

(6) |

or in even shorter form

|

(7) |

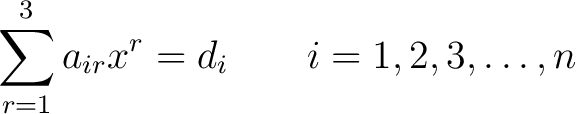

The system of equations

|

(8) |

represents  linear equations. linear equations.

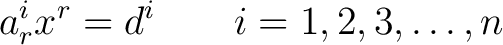

Einstein noticed that it was excessive to carry along the  sign in (8). we may rewrite (8) as sign in (8). we may rewrite (8) as

|

(9) |

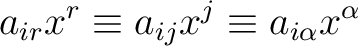

provided it is understood that whenever an index occurs exactly once both as a subscript and superscript a summation is indicated for this index over its full range of definition. In (9) the index  occurs both as a subscript (in occurs both as a subscript (in  ) and as a superscript (in ) and as a superscript (in  ), so that we sum on ), so that we sum on  from from  to to  . In a four-dimensional spacetime ( . In a four-dimensional spacetime (

) summation indices range from 1 to 4. The index of summation is a dummy index since the final result is independent of the letter used. We can write ) summation indices range from 1 to 4. The index of summation is a dummy index since the final result is independent of the letter used. We can write

|

(10) |

We may also write (9) as

|

(11) |

where the element  belongs to the ith row and jth column of the matrix belongs to the ith row and jth column of the matrix

|

(12) |

[1] Lass, Harry. "Elements of pure and applied mathematics" New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, 1957.

This entry is a derivative of the Public domain work [1].

|