|

The notion of category may be defined in a form which only involves morphisms and does not mention objects. This definition shows that categories are a generalization of semigroups in which the closure axiom has been weakened; rather than requiring that the product of two arbitrary elements of the system be defined as an element of the system, we only require the product to be defined in certain cases.

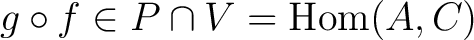

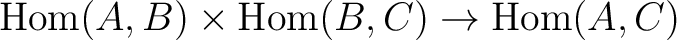

We define a category to be a set 1 (whose elements we shall term morphisms) and a function (whose elements we shall term morphisms) and a function  (which we shall term composition) from a subset (which we shall term composition) from a subset  of of

to to  which satisfies the following properties: which satisfies the following properties:

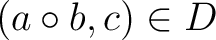

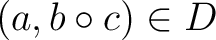

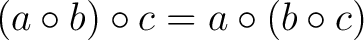

- 1. If

are elements of are elements of  such that such that

and and

and and

, then , then

. .

- 2 If

are elements of are elements of  such that such that

and and

, then , then

and and

and and

- 3a For every

, there exists an element , there exists an element  such that such that

-

and and

-

and and

- For all

such that such that

, we have , we have

. .

- 3a For every

, there exists an element , there exists an element  such that such that

-

and and

-

and and

- For all

such that such that

, we have , we have

. .

This definition may also be stated in terms of predicate calculus. Defining the three place predicate  by by  if and only if if and only if

and and

, our axioms look as follows: , our axioms look as follows:

That a category defined in the usual way satisfies these properties is easily enough established. Given two morphisms  and and  , the composition , the composition  is only defined if is only defined if

and and

for suitable objects for suitable objects  , i.e if the final object of , i.e if the final object of  equals the initial object of equals the initial object of  . The three hypotheses of axiom 1 state that the initial object of . The three hypotheses of axiom 1 state that the initial object of  equals the final objects of equals the final objects of  and and  and that the initial object of and that the initial object of  also equals the final object of also equals the final object of  ; hence the initial object of ; hence the initial object of  equals the final object of equals the final object of  so we may compose so we may compose  with with  . Axiom 2 states associativity of composition whilst axioms 3a and 3b follow from existence of identity elements. . Axiom 2 states associativity of composition whilst axioms 3a and 3b follow from existence of identity elements.

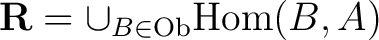

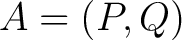

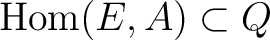

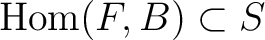

To show that the new definition implies the old one is not so easy because we must first recover the objects of the category somehow. The observation which makes this possible is that to each object  we may associate two sets: the set we may associate two sets: the set  of morphisms which have of morphisms which have  as initial object, as initial object,

, and the set , and the set  of morphisms which have of morphisms which have  as final object, as final object,

. Moreover, this pair of sets . Moreover, this pair of sets

determines determines  uniquely. In order for this observation to be useful for our purposes, we must somehow characterize these pairs of sets without reference to objects, which may be done by the further observation that, if we have two sets uniquely. In order for this observation to be useful for our purposes, we must somehow characterize these pairs of sets without reference to objects, which may be done by the further observation that, if we have two sets  and and  of morphisms such that of morphisms such that

if and only if if and only if  is defined for all is defined for all

and and

if and only if if and only if  is defined for all is defined for all

, then there exists an object , then there exists an object  which gives rise to which gives rise to  and and  as above. This fact may be demonstrated easily enough from the usual definition of category. We will now reverse the procedure, using our axioms to show that such pairs behave as objects should, justifying defining objects as such pairs. as above. This fact may be demonstrated easily enough from the usual definition of category. We will now reverse the procedure, using our axioms to show that such pairs behave as objects should, justifying defining objects as such pairs.

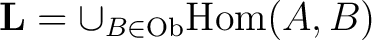

Returning to our new definition, let us now define

, ,

, ,

, and , and

as follows: as follows:

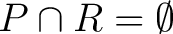

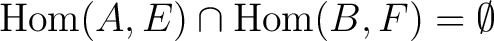

We now show that, if

then either then either

or or  . Suppose that . Suppose that

and and

. Then there exists a morphism . Then there exists a morphism  such that such that  and and  . By the definition of . By the definition of  , there exist morphisms , there exist morphisms  and and  such that such that

and and

. By definition of . By definition of  , we have , we have

and and

. If . If  , then , then

so, by axiom 1, so, by axiom 1,

, i.e. , i.e.

. Likewise, switching the roles of . Likewise, switching the roles of  and and  we conclude that, if we conclude that, if  , then , then  . Hence . Hence  . .

Making an argument similar to that of last paragraph, but with  instead of instead of  and and  instead of instead of  , we also conclude that, if , we also conclude that, if

then either then either

or or  . Because of axiom 3a, we know that, for every . Because of axiom 3a, we know that, for every  , there exists , there exists  such that such that

and, by axiom 3b, there exists and, by axiom 3b, there exists  such that such that

. Hence, the sets . Hence, the sets  and and  are each partitions of are each partitions of  . .

Next, we show that, if

and and  , then , then

. By definition, there exists a morphism . By definition, there exists a morphism  such that such that

, so , so

and and

. Now suppose that . Now suppose that

. This means that . This means that

. By axiom 1, we conclude that . By axiom 1, we conclude that

, so , so

. Likewise, switching the roles of . Likewise, switching the roles of  and and  in the foregoing argument, we conclude that, if in the foregoing argument, we conclude that, if

, then , then

. Thus, . Thus,

. .

By a similar argument to that of the last paragraph, we may also show that, if

and and  , then , then

. Taken together, these results tell us that there is a one-to-one correspondence between of . Taken together, these results tell us that there is a one-to-one correspondence between of  and and  — to each — to each

, there exists exactly one , there exists exactly one

such that such that

and vice-versa. In light of this fact, we shall define and object of our category to be a pair and vice-versa. In light of this fact, we shall define and object of our category to be a pair  of subsets of of subsets of  such that such that  if and only if if and only if

for all for all  and and  if and only if if and only if

for all for all  . Given two objects . Given two objects  and and  , we define , we define

. We now will verify that, with these definitions, our axioms reproduce the defining properties of the standard definition of category. . We now will verify that, with these definitions, our axioms reproduce the defining properties of the standard definition of category.

Suppose that  and and  and and  are objects according to the above definition and that are objects according to the above definition and that

and and

. Then . Then  and and  . By the way we defined our pairs, . By the way we defined our pairs,

, so , so  is defined. Let is defined. Let  be any element of be any element of  . Since . Since  , it follows that , it follows that

. Since . Since

as well, it follows from axiom 2 that as well, it follows from axiom 2 that

, so , so

. Let . Let  be any element of be any element of  . Since . Since  , it follows that , it follows that

. Since . Since

as well, it follows from axiom 2 that as well, it follows from axiom 2 that

, so , so

. Hence, . Hence,

. Thus, . Thus,  is defined as a function from is defined as a function from

. .

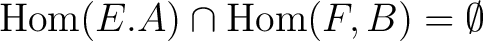

Next, suppose that  and and  are distinct objects. By the properties described earlier, are distinct objects. By the properties described earlier,

and and

. Let . Let  and and  be two objects. Since be two objects. Since

and and

, it follows that , it follows that

. Likewise, since . Likewise, since

and and

, it follows that , it follows that

. Hence, it follows that, given four objects . Hence, it follows that, given four objects  , we have , we have

unless unless  and and  . .

[more to come]

Footnotes

- 1

- For simplicity, we will only consider small categories here, avoiding logical complications related to proper classes.

|