|

The Calculus of Variations owed its origin to the attempt to solve a very interesting and rather narrow class of problems in Maxima and Minima, in which it is required to find the form of a function such that the definite integral of an expression involving that function and its derivative shall be a maximum or a minimum.

Let us consider three simple examples: The Shortest Line, The Curve of Quickest Descent, and The Minimum Surface of Revolution.

The Shortest Line. Let it be required to find the equation of the shortest plane curve joining two given points. The Shortest Line. Let it be required to find the equation of the shortest plane curve joining two given points.

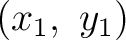

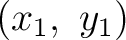

We shall use rectangular coordinates in the plane in question taking one of the points as the origin. Call the coordinates of the second point

. .

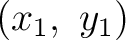

If  is a curve through is a curve through  and and

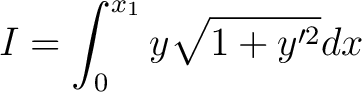

and and  is the length of the arc between the points, obviously is the length of the arc between the points, obviously

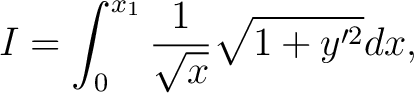

or

|

(1) |

and we wish to determine the form of the function  so that this integral shall be a minimum. so that this integral shall be a minimum.

The Curve of Quickest Descent. Let it be required to find the form of a smooth curve lying in a vertical plane and joining two given points, down which a particle starting from rest will slide under gravity from the first point to the second in the least possible time. The Curve of Quickest Descent. Let it be required to find the form of a smooth curve lying in a vertical plane and joining two given points, down which a particle starting from rest will slide under gravity from the first point to the second in the least possible time.

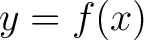

We shall use rectangular axes in the vertical plane taking the higher point as the origin and taking the axis of  downward. Call the coordinates of the second point downward. Call the coordinates of the second point

. .

Let  be a curve through be a curve through  and and

and use the well-known fact that and use the well-known fact that

the velocity of the moving particle at any time, is the velocity of the moving particle at any time, is

. .

We have

whence

and

Let

|

(2) |

and the form of the function  is to be determined so that this integral shall be a minimum. is to be determined so that this integral shall be a minimum.

The Minimum Surface of Revolution. Given two points and aline which are co-planar, let it be required to find the form of a curve terminated by the two points and lying in the plane which, by its revolution about the given line, shall generate a surface of the least possible area. The Minimum Surface of Revolution. Given two points and aline which are co-planar, let it be required to find the form of a curve terminated by the two points and lying in the plane which, by its revolution about the given line, shall generate a surface of the least possible area.

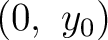

Take the line as the axis of  and use an axis of and use an axis of  through one of the points. Call the coordinates of the points through one of the points. Call the coordinates of the points  , and , and

. Let . Let  be a curve through be a curve through

and and

. .

If  is the area of the surface of revolution generated by the curve, is the area of the surface of revolution generated by the curve,

Let

|

(3) |

and we wish to determine the form of the function  so that so that  shall be a minimum. shall be a minimum.

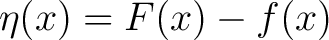

The three problems just considered are special cases of what we shall call our fundamental problem which is, to determine the form of the function  so that if so that if  , ,

shall be a maximum or a minimum;  being a given function and being a given function and  and and  being given constants, as are being given constants, as are  and and  , the corresponding values of , the corresponding values of  . .

In ordinary problems in maxima and minima  is a given function and we wish to find a value, is a given function and we wish to find a value,  , of , of  for which for which  is greater, if we seek a maximum, less, if we seek a minimum, than for neighboring values of is greater, if we seek a maximum, less, if we seek a minimum, than for neighboring values of  ; that is, for values of ; that is, for values of  differing from differing from  by a sufficiently small amount whether that amount is positive or negative.

by a sufficiently small amount whether that amount is positive or negative.

In our new problems, to speak in geometrical language, we have to find the form of a curve for which our integral,  , is greater or less than for any neighboring curve having the same end-points. , is greater or less than for any neighboring curve having the same end-points.

Let us now attack our first problem, that of the shortest line. We have to find the form of the function  so that if so that if

shall be a minimum when shall be a minimum when  . .

Let  be any other continuous curve joining the given points, and let be any other continuous curve joining the given points, and let

. .

Then

is our curve is our curve  . Consider the curve . Consider the curve

where where  is a parameter independent of is a parameter independent of  . .

For any particular value of  the curve the curve

is one of a family of curves including is one of a family of curves including  for for  and and  for for  . .

By taking a sufficiently small value for  we can make we can make

less in absolute value for that and all less values of less in absolute value for that and all less values of  , and for all values of , and for all values of  between 0 and between 0 and  , than any previously chosen quantity , than any previously chosen quantity  ; and for such values of ; and for such values of  the curve the curve

is said to be a curve in the neighborhood of is said to be a curve in the neighborhood of  . .

If  and and  are given, are given,  , the , the  for any one of our curves for any one of our curves

,is ,is

and  is a function of is a function of  only. only.

A necessary condition that  should be a minimum when should be a minimum when  is well known to be that is well known to be that

should be zero when should be zero when  . This condition we shall express as . This condition we shall express as

. .

Since the limits 0 and  are constants are constants

and

Integrating by parts

since  vanishes when vanishes when  and when and when  . .

A necessary condition that  shall be less than shall be less than  for some value of for some value of  and for all less values of and for all less values of  no matter what no matter what  may be, in which case the length of the curve may be, in which case the length of the curve  is less than that of any neighboring curve, is that is less than that of any neighboring curve, is that

independently of independently of  , i.e. that , i.e. that

no matter what the form of the arbitrary function  . .

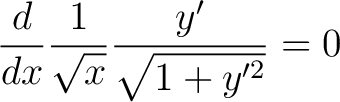

This condition will be satisfied if and only if

and we thus are led to a differential equation of the second order between  and and  . .

Its solution will express  as a function of as a function of  involving two arbitrary constants. involving two arbitrary constants.

whence

a constant;

The required curve is to pass through  and and

and thus we are able to determine and thus we are able to determine  and and  . .

Hence

; and our curve is a straight line through the given points. ; and our curve is a straight line through the given points.

If certain other conditions, depending on the fact that when  is a minimum is a minimum

must be positive, are satisfied, must be positive, are satisfied,

must be the required shortest line. must be the required shortest line.

As our necessary conditions gave us but a single solution it is clear that if there is any shortest line it must be our line

. .

We may note in passing that in simplifying

by integration by parts we tacitly assumed that by integration by parts we tacitly assumed that  and and  were continuous and had continuous first derivatives over the range of integration. were continuous and had continuous first derivatives over the range of integration.

We can deal with the general problem formulated previously precisely as we have dealt with the shortest line problem.

Let it be required to determine the form of the function  so that so that  shall make shall make

a maximum or a minimum; given that  when when  and and  when when  . .

As in the last section let

, and consider the family of curves , and consider the family of curves

Let

Let

and

must be made equal to zero. must be made equal to zero.

Integrating by parts,

since  vanishes when vanishes when  and when and when  . .

must be zero independently of the form of must be zero independently of the form of  therefore therefore

and as before we are led to a differential equation of the second order which if solved gives  as a function of as a function of  involving two arbitrary constants which must be determined from the facts that involving two arbitrary constants which must be determined from the facts that  when when  and and  when when  . This differential equation is known as Lagrange's equation and it is a necessary condition that . This differential equation is known as Lagrange's equation and it is a necessary condition that  should be a maximum or a minimum. should be a maximum or a minimum.

Any particular solution of Lagrange's Equation is called an extremal, and if the given problem has a solution it is that extremal which passes through the given end-points.

If  is a function of is a function of

only Lagrange's Equation becomes only Lagrange's Equation becomes

Whence

a constant, and the extremals are straight lines; and therefore the required solution is the straight line through the given end-points as before.

The problems of  and and  can be solved by substituting in Lagrange's Equation the appropriate value of can be solved by substituting in Lagrange's Equation the appropriate value of  and then solving the resulting equation. and then solving the resulting equation.

For the curve of quickest descent

Lagrange's Equation becomes

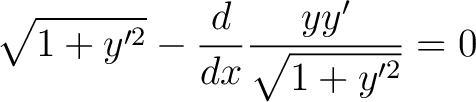

|

(4) |

For the minimum surface

Lagrange's Equation becomes

|

(5) |

We shall reserve the solving of (4) and (5) for a later article.

- 1

- Byerly, Willian E., Introduction to the Calculus of Variations. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1917.

This entry is a derivative of the Public domain work [1]

|